Webmaster Notes

Isabella Raymond's first husband was John Mayne.

Archibald Dundonald, 9th Earl of Dundonald, was not a wealthy man according to a biography. He did invent the Coal Tar process but failed to make much mony from it. There are stories of he and Isabella being extorted by Dundonald's business partner. "swindled by George Glenny". "By 1799, they gained possession of £23,000 acquired from the fortune of Archibald's marriage. "

There is another Isabella Raymond (G4 on the Tree), the sister Samuel Millbank (G2) and Oliver Raymond (should be G3 on Tree) and Margaretta Cave Raymond. This Isabella is the niece of Lady Dundonald (F3).

Isabella Raymond (G4) was married to Henry Yeates Smythies - see also The records of the Smythies Family.

Isabella Right Honourable Countess Dundonald - and Belchamp Walter

Isabella Raymond b.17?? m.1768 & 1774 d.1808

This page describes activity in Belchamp Walter in the 18th Century and

that of the country at the Industrial Revolution.

Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of Dundonald was the entrepreneur inventor involved with the coal tar process.

The connection is not obvious when you visit St. Mary's Church. You may

wonder what the significance of

Isabella Right Honourable Countess Dundonald is on the plaque in

the church. You may have also made an Internet search to find out why.

Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of Dundonald married Isabella, daughter of

Samuel (Junior of Belchamp Hall), on 12 April 1788.

This was is second marriage the first was to Anne Gilchrist,

daughter of Captain James Gilchrist, on 17 October 1774. He married, thirdly, Anna Maria Plowden,

daughter of Francis Plowden,

in April 1819, this was after Isabella had died.

The Right Honurable Countess Isabella was interred in the family vault 1808

(22 on list) Samuel her brother was interred 1826.

Samuel, her father was interred 1767.

Top

This page is part of an on-going research project on the history of Belchamp Walter and

the manor of Belchamp Walter.

If you have found it making a web search looking for geneological or other information on the village then please bookmark this page and return

often as I am likely to make regular updates. If you delve deeper into this website you will find many other pages similar

to this one.

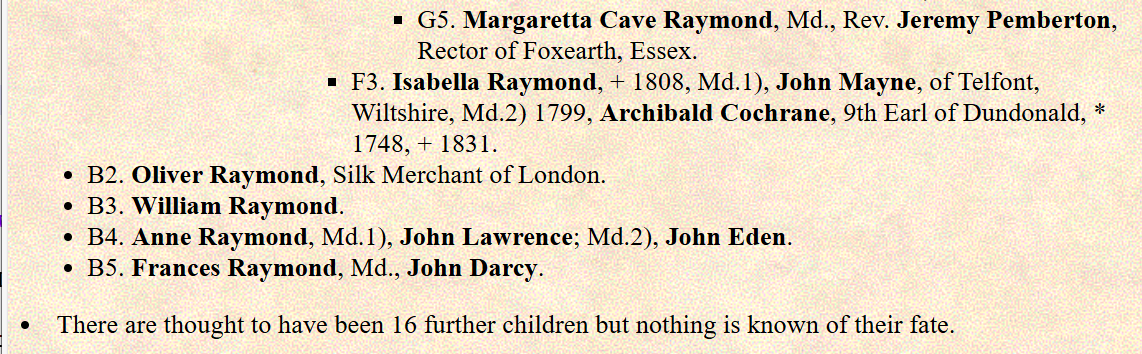

Below is an extract from the Alan Freer research:

Isabella is interred in the family vault in St. Mary's. The inscription on the

plaque in the chancel is "Isabella Right Honourable The Countess Dundonald d. 1808"

Recovery of the Manor from Thomas Ruggles

I need to check dates here, but there was the re-purchase of the Manor (lordship) and renovations of

St Mary's.

Archibald Cochrane was a Scotish Nobleman and inventor. He was the sucessor of the 8th Earl of Dundonald

and had little money.

His invention was that of coal tar that although patented by him it was never captialised and while adopted by the Royal Navy

did not result in a source of income for himself or the family.

He died impoverished in Paris in 1831.

Quote from, the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society:

There may however have been some revenue from the coal tar and other inventions:

The Earl of Dundonald

"Probably the first serious attempt to manufacture coal tar was made by Archibald Cochrane, the ninth Earl of

Dundonald.

The Earl was a self-taught inventor, who sadly never made the fortune he deserved from the process of manufacturing

tar

from coal at his estate at Culross Abbey, near Edinburgh. Throughout the 18th century, the Baltic Powers had virtually a

monopoly on the supply of wood tar and pitch, and they were thus in a position to exert diplomatic pressure on a nation

that was increasingly dependent for its prosperity on shipping. This was clearly an undesirable situation. Furthermore,

during the Napoleonic wars, the increased demand for wood tar for the large numbers of ships being built could not be satisfied,

and the situation was further exacerbated by the American War of Independence which adversely affected supplies of wood tar

from that country. The need for a substitute was the principal reason for Dundonald’s research.

He used all his financial

resources to construct a plant for decomposing coal by heating it in the absence of air in a closed vessel known as a retort

(the process was later called carbonisation). Coke, a valuable fuel, remained in the retort.

British Patent 1291 was granted

him in 1781 for ‘… a method of extracting or making tar, pitch and essential oils … from pit coal.’

"

Dundonald had another tar works at Muirkirk, which was managed by his cousin John Macadam, the inventor of

macadamised roads.

There were five more works in the Midlands, including one at Dudley Wood and one at Calcutts in Shropshire.

Then Dundonald began to suffer financial problems and, by 1785, his tar was being widely marketed by the

British Tar Company.

He suffered a further commercial setback when the Admiralty lost interest in tar, favouring the use of copper to

protect ships hulls.

The builders of new ships were not particularly interested either, declaring that, "The worm is our best friend",

meaning that

they made more money from repairing ships than they did from building them. Most of Dundonald’s tar was sold to

industry.

In the 1790s, Dundonald set up a works at Bow Common in East London. Interestingly, one of Dundonald’s descendants,

Thomas Barnes Cochrane, Earl of Dundonald, was granted a patent in 1863 referring to improvements in the production of

hydrocarbons from gas tar.

Dundonald’s experiments in the manufacture of tar from coal became interesting when he fitted a gun barrel to the delivery

pipe leading from his condenser. On applying a source of ignition to the end of the gun barrel, a brilliant light blazed out.

He had discovered that, in addition to tar and other chemicals, his process produced a gas that burned with a luminous flame.

But because the objective of his research was to increase the revenue from coal by manufacturing tar and pitch from it,

he failed to recognise the commercial potential of the gas as an illuminant; it was left to others to develop his discovery

and grow rich from it. He did, however, light one room of his house with it – as a novelty "to amaze" his guests.

In 1782 Dundonald described his process to the well-known partnership of Matthew Boulton and James Watt, hoping that he might

persuade them to invest in it. Boulton did in fact visit Dundonald in Scotland in the following year to discuss the matter,

but for some reason the partners showed little interest in his discovery.

But Dundonald’s process soon attracted wider interest. For example, in 1791 the Society of Arts awarded a prize to a William

Pitt for an account of a tar making plant at Dudley Wood Ironworks. There was a small number of tar distillers in business throughout

the country some years before towns gas was manufactured on a commercial scale, but the coal tar industry really began to develop

when large quantities of crude tar became available from the purification of gas. At first, most of the crude tar produced by the

new gas companies was sold to independent tar distillers, but some of them carried out tar distillation on a modest scale at their

own works; a practice which was to continue for many years.

"

It looks like rather generating any income for the Raymonds' Isabella lent Dundonald money which was repaid.

See: "Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of Dundonald (1748-1831) - Father of the British Tar Industry"

by Paul Luter

The 9th Earl of Dundonald was also the inventor of Potato Bread and other products related to chemical processing. He was

also associated with John Loudon McAdam again, you would have

thought that there was money to be made.

"

In December 1799, Alexander Brodie took over the kilns at The Calcutts from Dundonald and was marketing tar at nine pence per

barrel.

Consequently an income of nearly £700 from oils, resins and varnish paints was reached. At this time, Lady Isabel Dundonald

(nee Raymond) began to be swindled by George Glenny. Dundonald distaste for Glenny can be seen in his letters where he describes

him as "a scoundrel" and wanted a proper legal enquiry to be made as to his conduct. Meanwhile the partners in

the British Tar Company including Dundonald's brothers John and Basil had been declared bankrupt

"

In 1799 the British Tar Company was being managed by George Glenny, banker and gambler.

"

Dundonald found himself in a strange predicament at this time when John and Basil Cochrane, his brothers tried to saddle him with all their debts. By 1799, they gained possession of £23,000 acquired from the fortune of Archibald's marriage.

"

The Lordship of Belchamp Walter manor was sold to Thomas Ruggles in 1741

(by John III), this did not include the Manor house but presumably included some or all of the

surrounding land.

The money "swindled" from Isabella, and presumably the Rs was well over £1,000,000 in todays money.

Julian Fellows in

his book "Belgravia" was describing far smaller amounts in 1840's in his description of the Earl of Tavistocks

gambler son.

John Mayne St. Clere Raymond repurchased the Manoral lands

(presumably from Thomas Ruggles) in 1863??????

The Honywoods

The name Honywood appears on the family plaque in the church and the Alan Freer

family tree. There is a (possible) Honywood conection to Marks Hall, Coggeshall

The first Phillip Honywood died young in 1757. This Honywood was a brother of Samuel and Isabella.

St. Mary's Church at this time

Samuel (junior) - 1784-1826

Brosley and Sutton Coldfield

June 2022 - interest from Sutton Coldfield.

Brosley and Sutton Coldfield, the relevance of the link to oldcopper.org is not known,

are only 40 miles away from each other. Shropshire and East Midlands, Birmingham.

thepeerage.com - Darryl Lundy - Wellington, New Zealand

"

Archibald Cochrane, 9th Earl of Dundonald was born on 1 January 1748.2 He was the son of Thomas Cochrane,

8th Earl of Dundonald and Jane Stuart.3 He married, firstly, Anne Gilchrist, daughter of

Captain James Gilchrist, on 17 October 1774.2 He married, secondly, Isabella Raymond, daughter of

Samuel Raymond, on 12 April 1788.3 He married, thirdly, Anna Maria Plowden, daughter of Francis Plowden,

in April 1819.3 He died on 1 July 1831 at age 83 at

Paris, FranceG.3

"

He gained the rank of Cornet in 1764 in the 3rd Dragoons.2 He gained the rank of officer in the Royal Navy.2

He was an inventor.2 He succeeded as the 9th Earl of Dundonald [S., 1669] on 27 June 1778.2 He succeeded

as the 9th Lord Cochrane of Paseley and Ochiltrie [S., 1669] on 27 June 1778.2 He succeeded as the

9th Lord Cochrane of Dundonald [S., 1647] on 27 June 1778.2 He has an extensive biographical entry

in the Dictionary of National Biography.4