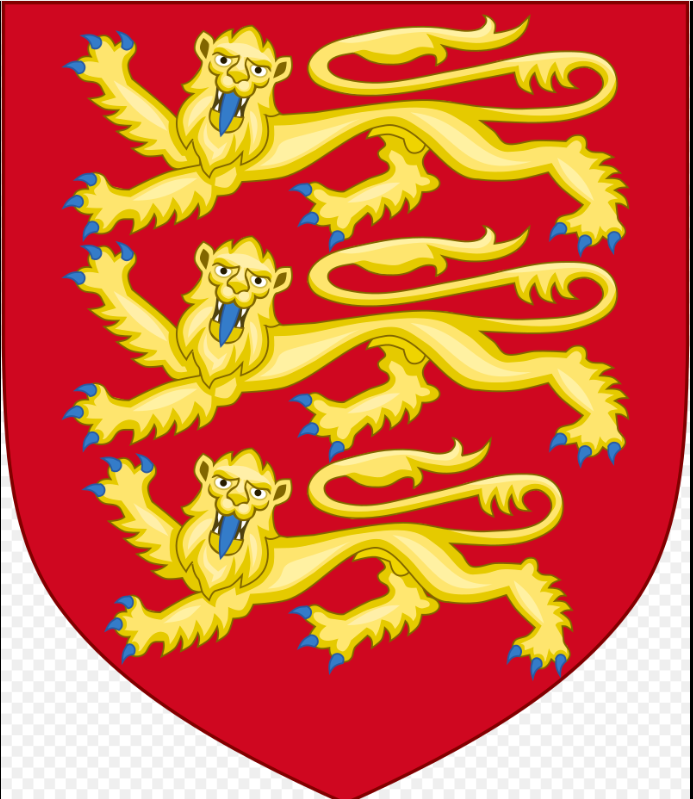

Edward II - reign 1307-1327

The reign of Edward II is significant in the history of Belchamp Walter in the

14th century. The story of the "Life and times of Sir John de Botetourt" and the reason that he has

a chantry chapel in the village church owes much to what happened over that time scale.

Edward II succeeded his father Edward I, "Hammer of the Scots", and had a "checkered" existance in his

time as monarch continuing the campaign in Scotland and his "relationships", both with his "favourites",

his queen and France.

Wikipedia says:

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from

1307 until he was deposed in January 1327.

The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir to the

throne following the death of his older brother Alphonso.

Beginning in 1300, Edward accompanied his father on

campaigns to pacify Scotland, and in 1306 he was knighted in a grand ceremony at Westminster Abbey.

Edward succeeded to the throne next year, following his father's death. In 1308, he married Isabella of France,

the daughter of the powerful King Philip IV, as part

of a long-running effort to resolve the tensions between the English and French crowns.

Top

Dispenser War

The two Hugh Dispensers are key to this time in English History, this is not counting the

first Hugh Dispenser (justiciar) 1st Baron le Despenser (1223 – 4 August 1265). Hugh Dispenser the elder

The Despenser War (1321–22) was a baronial revolt against Edward II of England led by the Marcher Lords

Roger Mortimer and Humphrey de Bohun. The rebellion was fuelled by opposition to Hugh Despenser

the Younger, the royal favourite.[nb 1] After the rebels' summer campaign of 1321, Edward was able to

take advantage of a temporary peace to rally more support and a successful winter campaign in southern Wales,

culminating in royal victory at the Battle of Boroughbridge

in the north of England in March 1322.

Edward's response to victory was his increasingly harsh rule until his fall from power in 1326.

Hugh le Despenser (1 March 1261 – 27 October 1326), sometimes referred to as "the Elder Despenser", was for

a time the chief adviser to King Edward II of England.[1] He was created a baron in 1295 and Earl of Winchester in

1322. One day after being captured by forces loyal to Sir Roger Mortimer and Edward's wife, Queen Isabella,

who were leading a rebellion against Edward, he was hanged and then beheaded.

Ordinances of 1311 - The Fourteenth Century, 1307–1399 May McKisac

May McKisac in her book "The Fourteenth Century" mentions that Hereford, Pembroke and John Botetourt

were instrumental in the insistance that Edward II adhered to the Ordinances of 1311

that were drawn up to control what Edward II could financially.

The Ordinances of 1311 (The New Ordinances, Norman: Les noveles Ordenances) were a series of regulations

imposed upon King Edward II by the peerage and clergy of the Kingdom of England to restrict the power

of the English monarch.[a] The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the

Lords Ordainers, or simply the Ordainers.[b] English setbacks in the Scottish war, combined with

perceived extortionate royal fiscal policies, set the background for the writing of the Ordinances

in which the administrative prerogatives of the king were largely appropriated by a baronial council.

The Ordinances reflect the Provisions of Oxford and the Provisions of Westminster from the late 1250s,

but unlike the Provisions, the Ordinances featured a new concern with fiscal reform,

specifically redirecting revenues from the king's household to the exchequer.

Sir John de Botetourts' role in this

The referenced to Hereford and Pembroke

are Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford and Aymer de Valence, 2nd Earl of Pembroke.

The IPM, Edward II - Vol 6, File 89 - references Aymer de Valence in

John Botetourts entry 257 from 1320 and the Manor of Great Kerbrok.

The manor of Iselhamstede

Hugh Despenser the younger. Ishampstead (in Chesham), Buckinghamshire [note the two spellings]

What did John and Maud de Botetourt have to do with this?

CP 25/1/19/74, number 5.

County: Buckinghamshire.

Place: Westminster.

Date: Two weeks from Easter, 17 Edward II [29 April 1324].

Parties: Hugh le Despenser the younger, querent, by Robert de Swyneburn', put in his place by the lord king's

writ, and John Butetourt' and Maud, his wife, deforciants.

Property: The manor of Iselhamstede and 2 knights' fees in and the advowson of the chapel of the

same vill.

Action: Plea of covenant.

Agreement: John and Maud have acknowledged the manor, fees and advowson, together with the homages and all

services of Robert le Low and Alice, his wife, and Lawrence del Brok' and their heirs, in respect of all the

tenements which they held before of John and Maud in the aforesaid vill, to be the right of Hugh, and have

rendered the manor and advowson to him in the court, to hold to Hugh and his heirs, of the chief lords for ever.

Warranty: Warranty by John and Maud for themselves and the heirs of Maud.

For this: Hugh has given them 100 pounds sterling.

Note: This agreement was made in the presence of Robert and Alice, and they did fealty to Hugh in the court.

Isabella and Roger Mortimer

Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer -

Despenser War

Piers Gaveston

Lords Ordainers

Sir John de Botetourt was associated with these"magnates".

Wikipedia:

The Ordainers were elected by an assembly of magnates, without representation from the commons.[e]

They were a diverse group, consisting of eight earls, seven bishops and six barons – twenty-one in all.[f]

There were faithful royalists represented as well as fierce opponents of the king.[15]

Among the Ordainers considered loyal to Edward II was John of Brittany, Earl of Richmond who was also by

this time one of the older remaining earls. John had served Edward I, his uncle, and was Edward II's first

cousin. The natural leader of the group was Henry Lacy, Earl of Lincoln. One of the wealthiest men in the

country, he was also the oldest of the earls and had proved his loyalty and ableness through long service

to Edward I.[17] Lincoln had a moderating influence on the more extreme members of the group, but with

his death in February 1311, leadership passed to his son-in-law and heir Thomas of Lancaster.[18] Lancaster

– the king's cousin – was now in possession of five earldoms which made him by far the wealthiest man

in the country, save the king.[19] There is no evidence that Lancaster was in opposition to the king

in the early years of the king's reign,[20] but by the time of the Ordinances it is clear that

something had negatively affected his opinion of King Edward.[g]

Lancaster's main ally was Guy Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. Warwick was the most fervently and consistently

antagonistic of the earls, and remained so until his early death in 1315.[22] Other earls were more

amenable. Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, was Gaveston's brother-in-law and stayed loyal

to the king.[23] Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, would later be one of the king's most central

supporters, yet at this point he found the most prudent course of action was to go along with the

reformers.[24] Of the barons, at least Robert Clifford and William Marshall seemed to have royalist leanings.

Kathryn Warner - the events, issues and personalities of Edward II's reign, 1307-1327.

I came across Kathryn's blog when looking for the sisters of Edward II. This was prompted by a search for the book

"Edward II's Nieces, The Clare Sisters Powerful Pawns of the Crown" - was because that I had seen it in the bookshop

in Clare, Suffolk

and it looked interesting. My interest related to Edward II himself and the connection to Clare and Elizabeth de Burgh.

Controversy over the death of Edward II

Controversy rapidly surrounded Edward's death.[333] With Mortimer's execution in 1330, rumours began to

circulate that Edward had been murdered at Berkeley Castle. Accounts that he had been killed by the insertion of

a red-hot iron or poker into his anus slowly began to spread, possibly as a result of deliberate propaganda;

chroniclers in the mid-1330s and 1340s disseminated this account further, supported in later years by

Geoffrey le Baker's colourful account of the killing.[334] It became incorporated into most later

histories of Edward, typically being linked to his possible homosexuality.[335]

Most historians now dismiss this account of Edward's death, querying the logic in his

captors murdering him in such an easily detectable fashion