Domesday Rethought

Basing a historical record of a region of the UK on what can be found in the Domesday Survey is problematic.

Top

Some ambiguities and identifications among Domesday names (2012) - Duncan Probert, March 2012

A section of Duncan Probert's paper talks about Stansfield, Rougham, Nedging and Waldingfield

At times, the distributions revealed by comparing the Domesday material to that in PASE can reveal a pattern that seems meaningful but cannot fully be explained as yet.

Because inflectional endings are not consistently rendered in late spellings of Old English it is difficult to distinguish between the masculine name derived from crāwa ‘raven’ and the closely-related feminine name derived from OE crāwe ‘crow’.

Someone with the masculine form was recorded as holding a small estate at Stansfield in west Suffolk in 1066. The feminine form occurs as the matronymic for two post-Conquest minor tenants of Bury St Edmunds Abbey at Rougham.

These are the only instances of either form recorded in Domesday or its satellites, although obviously that’s not sufficient grounds to associate the individuals concerned. Nevertheless, when we look at the PASE corpus we find that the only related entry is for Crawe 1, who at the beginning of the eleventh century was

granted lands at Neding and Waldingfield by her kinswoman. It is notable that the

only places associated with the names Crawa and Crawe were all in western

Suffolk and less than 16 miles from each other, which raises the possibility that

some names had a very localized currency.

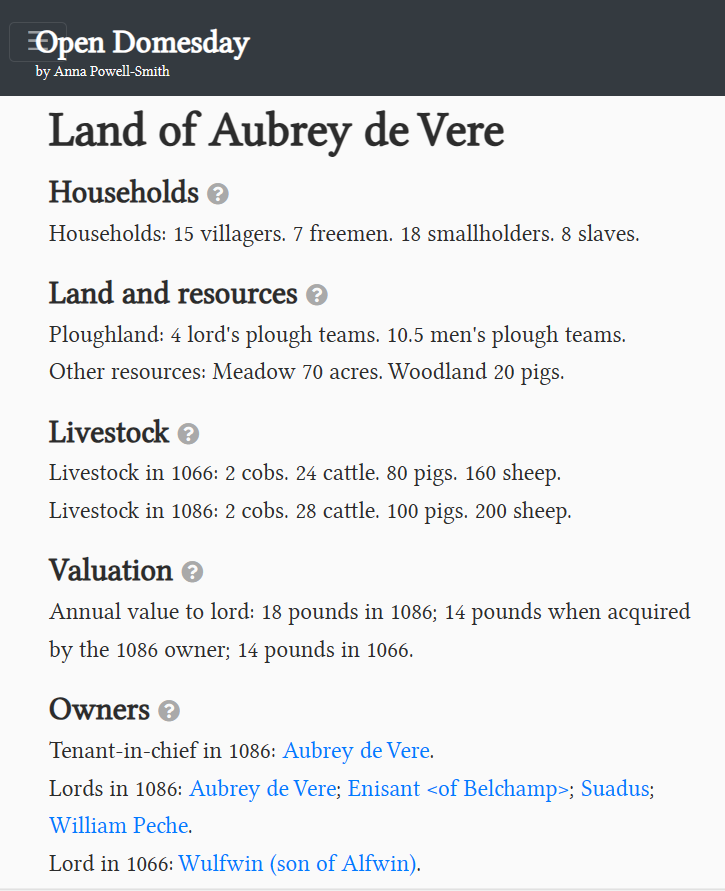

A Brief History of the Veres in England - The Veres of Normandy - RáGena C. DeAragon

A fuller analysis of RáGena's paper on the origins the de Vere family

An interesting comment about the Domesday book.

The very nature of the Domesday Book, especially entries in the more processed volume containing all

counties but Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk, makes it difficult to assess the order or date of acquisition. If

forced to guess, I think that he gained the tenancies in Berkshire and Hampshire from the king first–they

lie within 10 kilometers of the road between London and Southampton via Winchester, the route often

taken from by the court going to and from Normandy. One clue that he held at least one Hampshire manor

by 1070 comes from the entry for Hartley Wespall. Then perhaps he was enfeoffed by Geoffrey bishop of

Coutances. Next, by royal grant, the substantial estate of the Anglo-Saxon thegn Wulfwin that established

Aubrey as an important baron, possibly in the mid- to later 1070s but certainly by 1083. As a consequence

of that grant he seized land from Ramsey Abbey in Huntingdonshire. Only after he held land at Great

Canfield, Essex, as part of his barony did he seek from Count Alan another holding in that parish, as well

as the nearby Beauchamp Roding, to hold of the honor of Richmond.

Doing Things Beside Domesday Book - Carol Symes, October 2018

Again, having observed that it is too easy to quote Domesday a baseline for the history of a comunity is somewhat

a "cop-out", Carol Symes discusses this further:

Domesday Book is the collective name attached to two different bodies of text.

Colloquially known as “Great” and “Little” Domesday, they represent successive

documentary phases of the inquest undertaken by agents of William the Conqueror in 1086.1

The more famous (also known as “Exchequer Domesday”) is a condensed edition of the

inquest’s results. The other is an earlier artifact (a “circuit survey” in the parlance of

Domesday historiography) comprising more detailed information gathered from the East

Anglian shires of Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex.2

In the past decade or so, a growing body of

scholarship has established that analogous surveys of England’s other regions were also

prepared and eventually became the exemplars abbreviated and anthologized by Great

Domesday’s chief scribe. Thereafter, however, only the surveys contained in Little

Domesday were preserved, perhaps to make up for these specific counties’ absence from

Great Domesday.3